Attorneys who wish to enhance the comprehensibility of the “Statement of Facts” sections of their briefs should consider using timelines, dispute charts and pictures to engage readers and to highlight aspects of cases that would otherwise remain buried in seas of ink. As the “Practitioner’s Handbook for Appeals,” published by the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals so aptly states, “[n]othing is more discouraging to the judicial reader than a great expanse of print with no guideposts and little paragraphing.” The Handbook suggests short paragraphs, topic sentences, frequent headings and subheadings. In an appropriate case, the use of timelines, dispute charts and even pictures can enhance a “Statement of Facts” section, identify key issues, and encourage the judicial reader to become engaged in the text and facts of the case. In this post, I will endeavor to show how a timeline can help turn a great expanse of print or an inscrutable sea or words into a lucid explanation of the facts.

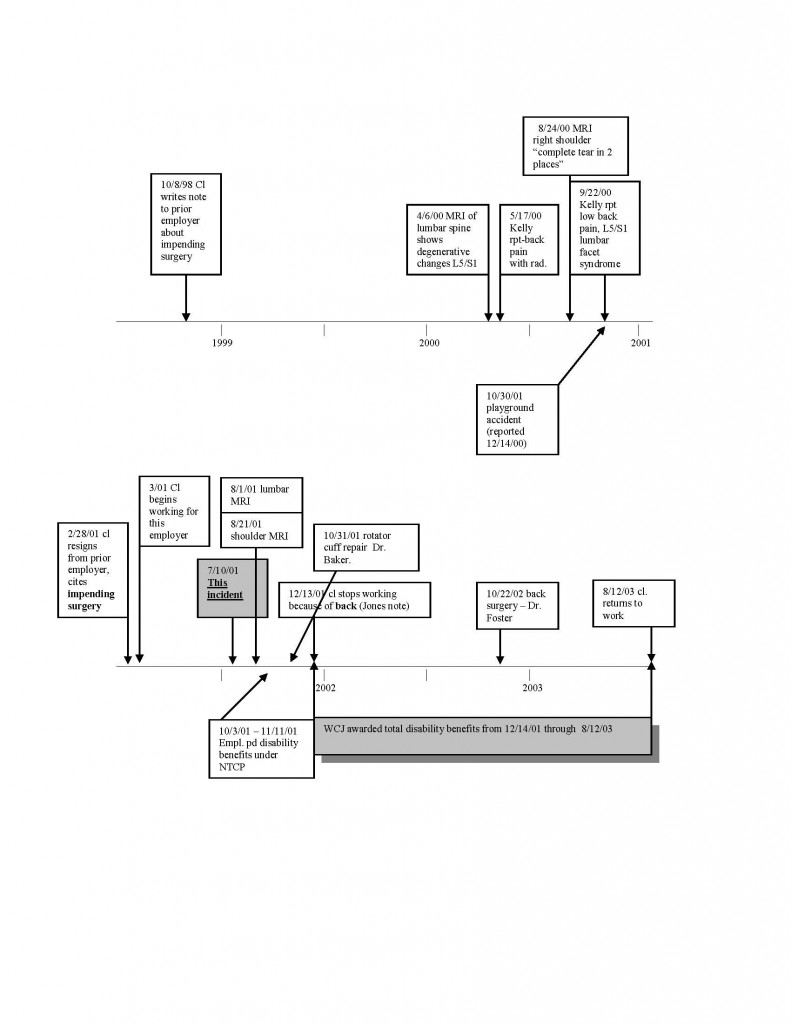

For example, let us assume that you are preparing a brief on appeal from a workers’ compensation board determination, and you wish to highlight the fact that the claimant had several injuries and conditions prior to the accident or injury that is the subject of the appeal. You could prepare a witness-by-witness summary, but that approach is strictly passé and, in fact, has been condemned by the appellate rules in several states. See, e.g., N.J. Court Rules, R. 2:6-2 (requiring that the “statement shall be in the form of a narrative chronological summary incorporating all pertinent evidence and shall not be a summary of all of the evidence adduced at trial, witness by witness.”(emphasis added)); Pa. R.A.P. 2117 (requiring a “closely condensed chronological statement, in narrative form, of all the facts which are necessary to be known . . .” (emphasis added)). Rather, you should describe the accidents and injuries in chronological order. To emphasize the point, you could prepare a timeline, either preceded by or followed up the text:

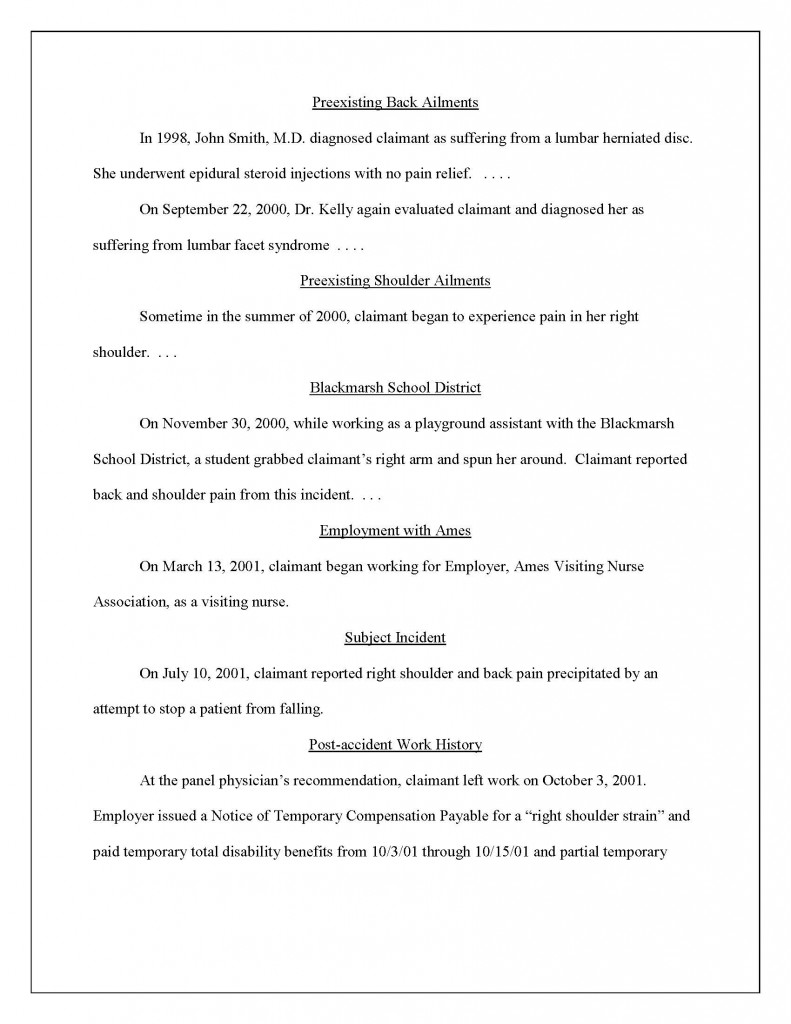

One could then prepare narrative to follow the timeline. The following example is interspersed with headings, thus heeding the admonition of the Seventh Circuit manual:

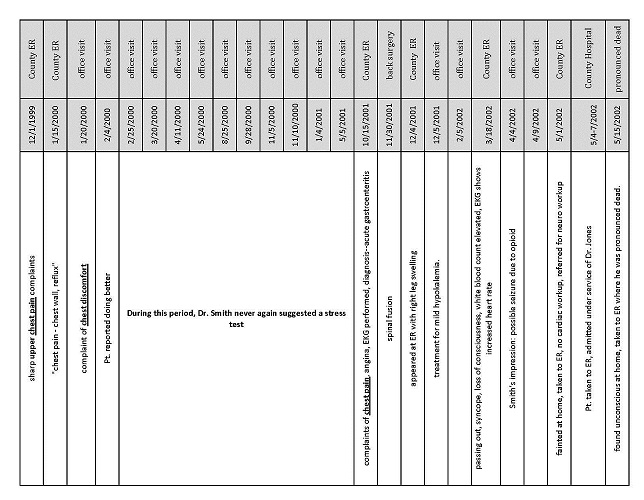

Suppose you represent a plaintiff in a medical malpractice case and you wish to emphasize the fact that a defendant physician waited an inordinate amount of time to order or even suggest a test. The following timeline makes the point more effectively than a jumble of words:

The placement of the words makes the point in a simple but effective manner.

A timeline is useful in cases involving complicated medical testimony, particularly when one wishes to emphasize key aspects of the chronology that might otherwise be lost. Obviously, if you represented the claimant in the first example or the defendant physician in the second, you would avoid using one. But the possible uses are many, and you might consider them, using Excel, Word or other programs as your tools for now. As technology expands, the truly interactive timeline with hyperlinks to evidence and trial testimony may soon become possible.

Recent Comments